Tardive Dyskinesia Symptoms: Common Signs and When to Seek Medical Care

Understanding Tardive Dyskinesia: A Quick Orientation and Outline

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a movement disorder marked by involuntary, repetitive motions that develop after prolonged exposure to medicines that block dopamine receptors, often prescribed for mood, psychosis, or severe nausea. The movements are typically choreoathetoid—writhing, twisting, or jerking—and tend to appear while awake, ease during sleep, and fluctuate with attention, emotion, and fatigue. In observational studies, TD risk rises with longer duration of treatment and higher cumulative exposure, and it appears more often in older adults and in those with additional medical vulnerabilities. Symptoms can persist even when the original medication is reduced or discontinued, which is one reason early recognition is valuable. Think of TD like a metronome you never set: the rhythm starts subtly, then grows louder in rooms where stress and stimulation echo.

Before we dive deep, here is the outline so you can scan, skim, or settle in as needed:

– Orofacial movements: how lips, tongue, jaw, and facial muscles participate, and how this affects eating, speaking, and dental health

– Limbs and trunk: from finger “piano-playing” and toe tapping to shoulder shrugs, hip rocking, and respiratory patterns

– Sensory and functional impact: the hidden burdens—discomfort, embarrassment, fatigue—and how symptoms change with context

– When to seek care and how TD is evaluated: red flags, the clinical exam, tracking tools, and a practical conclusion

It helps to note what TD is not. Acute dystonia—painful, sustained muscle spasms—can appear within hours or days of starting certain medicines, while TD usually emerges after months or years. Drug-induced parkinsonism causes slowed movement and stiffness plus a resting tremor, yet TD is more often irregular and dance-like. These distinctions matter because the strategy for reducing harm depends on the cause. If you are a patient or caregiver, your role is to recognize patterns: what moves, when it moves, how it interferes. The sections ahead translate medical jargon into everyday observations you can bring to a clinic visit, anchoring careful decisions rather than snap reactions.

Orofacial Movements: Mouth, Tongue, and Facial Signs You Can Recognize

Orofacial symptoms are the hallmark of TD and often the first signals people notice in mirrors, photos, or the small rituals of daily life. Common features involve the “buccal-lingual-masticatory” triad—cheek, tongue, and chewing motions—that dance together without permission. You might see lip smacking or pursing, tongue darting in and out (“fly-catching”), chewing without food, or jaw shifts that feel like a restless gear seeking a clutch. Blinking can accelerate, brows may furrow and release, and grimacing may punctuate conversations. These movements can be sporadic or near-continuous, sometimes pausing briefly with intense concentration only to rebound when attention drifts.

Why do these signs matter? Beyond visibility, orofacial TD can affect speaking, smiling, and swallowing. Taste and texture may feel “off” because the tongue is rarely still, and dentures or dental work can loosen or wear down from unplanned grinding. Meals can become a series of negotiations—choosing softer foods, swapping utensils, or timing bites for moments of relative calm. There is also the social echo: friends may misread movements as tics or nerves, and people can withdraw to avoid awkward questions. That isolation can be heavier than the movements themselves.

It helps to compare TD with similar conditions so you can describe what you see:

– Acute jaw or neck dystonia is often painful and sustained; TD tends to be less painful and more flowing or jerky.

– Tremor is rhythmic; TD is usually irregular, varying in amplitude and direction.

– Oromandibular dystonia can share jaw opening or closing; TD more commonly adds tongue protrusions and lip movements in a mixed, shifting pattern.

Try simple home observations you can later share with a clinician:

– Speak a tongue twister or read a paragraph aloud: do lip or tongue movements amplify?

– Take slow sips of water: do you notice tongue protrusions between sips?

– Chew gum for one minute: do movements temporarily “mask” under purposeful chewing, then reappear?

– Relax your face in a mirror for 30 seconds: do movements fade with focus and return when you look away?

These are not diagnostic tests, but they turn vague concerns into concrete notes. Keep in mind that TD can coexist with other movement phenomena, and only a qualified clinician can diagnose it. Your observations simply set the stage for a careful evaluation and a more tailored plan.

Limb and Trunk Symptoms: From Subtle Twitches to Rocking and Swaying

While the face often gets attention, TD can involve the arms, legs, shoulders, hips, and torso. Finger “piano-playing,” hand writhing, wrist rotations, or forearm twitches may appear during rest, grow with distraction, and sometimes settle during goal-directed movement. In the legs, look for toe tapping, ankle turning, foot inversion and eversion, or restless crossing and uncrossing. The trunk can rock forward and back or side to side; shoulders might shrug rhythmically; the pelvis may thrust subtly when seated. Gait can look dance-like, with extra steps or a sway that is out of sync with the task at hand.

Breathing and voice can also be affected. Some people develop intermittent grunts, irregular breaths, or a sensation of chest movements that do not match the pace of walking or talking. These respiratory signs can be easy to miss, attributed to anxiety or habit, yet they matter because they influence comfort, speech timing, and fatigue. If breath-related movements feel distressing or interfere with swallowing, that is a prompt to seek care promptly.

TD movements in the limbs and trunk often intensify with stress, strong emotions, caffeine, or sleep loss, and they commonly ease with relaxation or during sleep. This waxing and waning can lead to misunderstandings: on “quiet” days, symptoms seem trivial, while on tough days they feel overwhelming. Comparing TD with other conditions helps clarify the pattern:

– Resting tremor (as seen in parkinsonism) is rhythmic and classically involves “pill-rolling” of the fingers; TD is irregular, flowing, and multi-directional.

– Akathisia centers on inner restlessness with an urge to move; TD movements can occur without the same inner drive, and people may not feel relief after moving.

– Myoclonus causes lightning-like jerks; TD tends to feature sustained or slow writhing interspersed with quicker fragments.

When describing limb and trunk symptoms to a clinician, think in short stories: “My left foot turns inward when I watch TV,” “My shoulders rock when I’m on the phone,” or “I notice finger writhing that pauses when I knit but returns when I stop.” These narratives, especially when paired with short video clips taken in similar lighting and at a similar time of day, can be more informative than a one-time exam in a quiet room.

The Hidden Burden: Sensory Urges, Emotions, and Daily Function

Movements are only part of the TD experience. Many people report pre-movement sensations—an itch-like urge, pressure, or inner “buzz” that predicts a lip purse or a shoulder rock. These urges can be subtle yet exhausting, like holding back a sneeze that never quite arrives. Emotional ripples follow: frustration when a work task takes longer, embarrassment in a quiet classroom, or anxiety before a video meeting. Over time, this can reshape social plans, self-image, and the confidence to try new activities.

Daily function is where symptoms become real. Eating may take longer because the jaw will not cooperate, and speech may feel choppy if the tongue insists on its own rhythm. Fine motor tasks like typing or buttoning a shirt can be slowed by finger writhing. Posture-related movements can trigger back or neck soreness by day’s end. Sleep itself is often spared, but the anticipation of daytime symptoms can disrupt bedtime routines. When movements involve the eyes—excessive blinking or spasms—reading endurance drops and screens become tiring.

To make these challenges visible in care visits, consider structured note-taking:

– Frequency: how often do movements show up across a typical day?

– Triggers: stress, caffeine, fatigue, conversations, sustained attention, or specific tasks?

– Interference: eating, speaking, walking, work speed or accuracy, social interactions?

– Safety: tongue or cheek biting, near-choking episodes, falls, or joint pain?

– Context: new medicines, dosage changes, or missed doses in the weeks before movements emerged?

Small, practical steps can soften the edges while you pursue medical evaluation. Some people find that scheduling breaks before stressful tasks reduces symptom surges. Warm compresses can ease muscle aches that accrue from repetitive motion. Choosing softer foods on high-symptom days conserves energy. A discreet fidget object, a stress-breathing routine, or ambient music can shift attention and lower tension enough to quiet movements temporarily. None of these replace clinical care, but they let you reclaim pockets of control while the diagnostic and treatment process unfolds.

When to Seek Care and Conclusion: Recognize, Record, Reach Out

Seek medical attention if new involuntary movements appear after weeks to months of treatment with a dopamine-blocking medicine, especially if they interfere with eating, speech, walking, or work. Treat it as urgent if movements involve breathing or swallowing, force the eyes shut for long periods, cause repeated tongue or cheek injuries, provoke severe neck or back arching, or lead to falls. If a recent medication change coincides with symptom onset—whether a dose increase, decrease, or discontinuation—share that timeline; TD can emerge or fluctuate around such transitions.

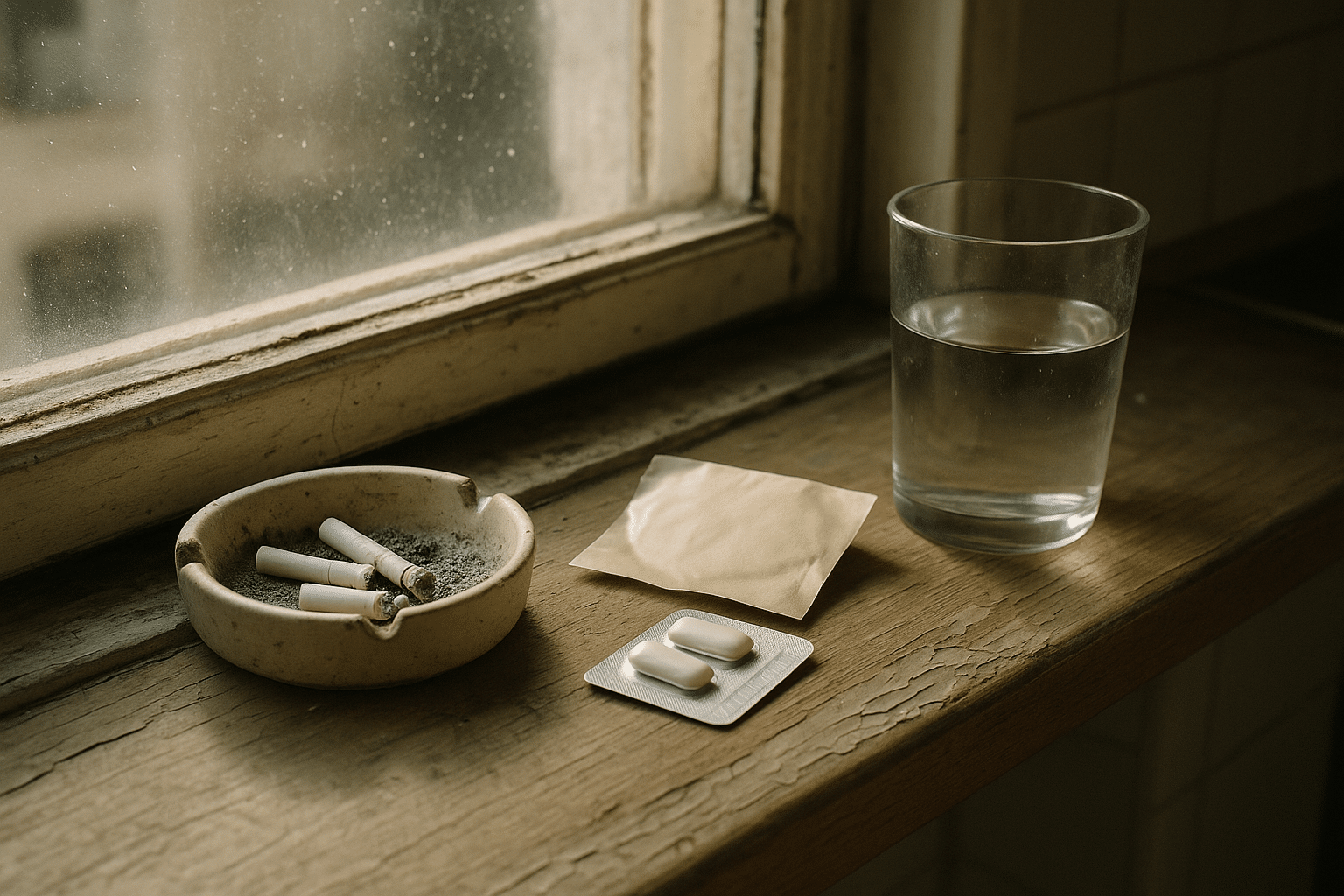

During evaluation, clinicians often use structured tools such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) to rate severity across body regions. Expect questions about medication history, including total duration of exposure, highest doses reached, and any prior movement symptoms. A careful exam distinguishes TD from look-alikes like acute dystonia, drug-induced parkinsonism, essential tremor, or functional movement disorders. Sometimes, short videos captured at home in typical settings reveal patterns that a quiet exam room conceals. It is also common to review other health factors—metabolic status, substance use, or coexisting neurological conditions—that can shape symptom expression.

One key principle: do not change or stop prescribed medicines on your own. Abrupt shifts can worsen symptoms or destabilize the condition the medicine treats. Discuss options with a clinician; in some cases, adjusting doses, switching within a drug class, or considering treatments specifically studied for TD may be appropriate. Because stress reliably amplifies movements, building a simple routine—sleep regularity, hydration, brief daytime movement, and a wind-down ritual—provides a supportive backdrop for medical care.

Conclusion—Recognize, Record, Reach Out: TD’s symptoms can feel like an unwanted soundtrack, but naming the notes changes the experience. Recognize patterns in your face, limbs, trunk, and breath. Record brief observations and videos so your story is clear in the clinic. Reach out early when movements affect safety, meals, or confidence. With informed tracking and timely guidance, you can reduce risk, preserve function, and make shared decisions that respect both symptom control and overall well-being.